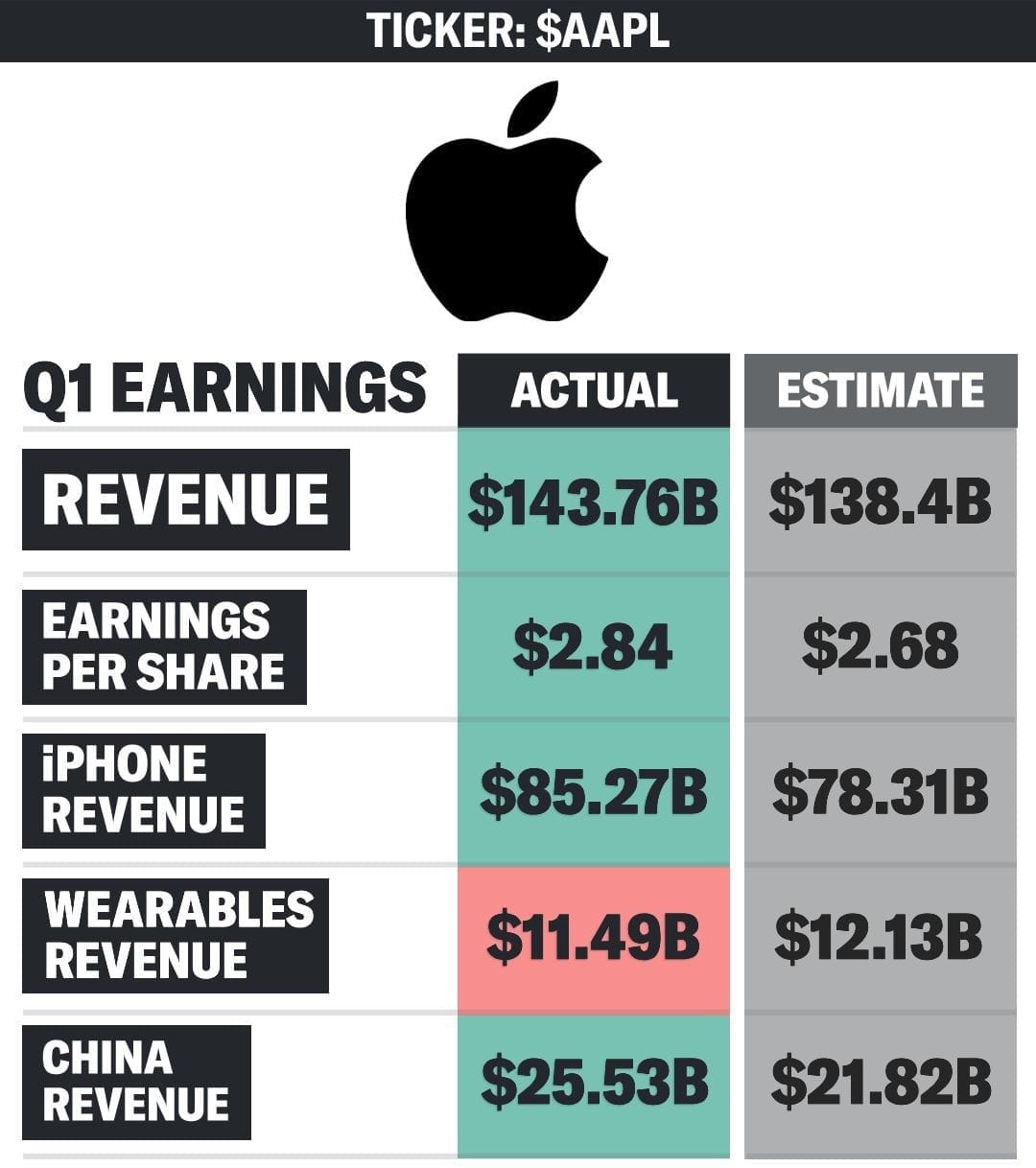

Apple just crossed a milestone that should have every tech analyst rethinking what this company actually is. In Q3 2025, services revenue hit $27.4 billion—a 13% year-over-year increase that solidly established the annual run rate well above $100 billion. To put that in perspective, Apple's services division alone would rank around 40th on the Fortune 500, ahead of Morgan Stanley and Johnson & Johnson.

But here's the uncomfortable question nobody at Apple Park wants to answer: At what point does optimizing for recurring revenue fundamentally compromise the thing that made Apple, well, Apple?

The Numbers Don't Lie (But They Don't Tell the Whole Story Either)

Let's start with the stark reality: Services now generates a 74-75% gross margin compared to just 35-36% for hardware. When you're pulling in three-quarters pure profit on every services dollar versus barely a third on devices, the financial incentives become almost irresistible. Last quarter, Apple made about $22 billion in profit from products and $18 billion from services—the closest those lines have ever been.

We're approaching an inflection point where Apple will report more total profit from services than from the hardware that built the company's reputation. And when that day comes—probably within the next year—we need to ask: Is Apple still a products company, or has it crossed some invisible Rubicon?

The services portfolio is impressive in its breadth: the App Store (including that controversial 15-30% cut), Apple Music (108 million subscribers), Apple TV+ (around 25 million paid subscribers, plus another 50 million on promotional access), iCloud storage, AppleCare, Apple Arcade, Apple News+, Apple Fitness+, Apple Pay, and various licensing deals—most notably the estimated $18-20 billion annual payment from Google to remain the default search engine.

Over 1 billion paid subscriptions now run through Apple's ecosystem. That's a phenomenal achievement. It's also a ticking time bomb of dependency.

The Bundle Paradox: Hiding Weakness Behind Convenience

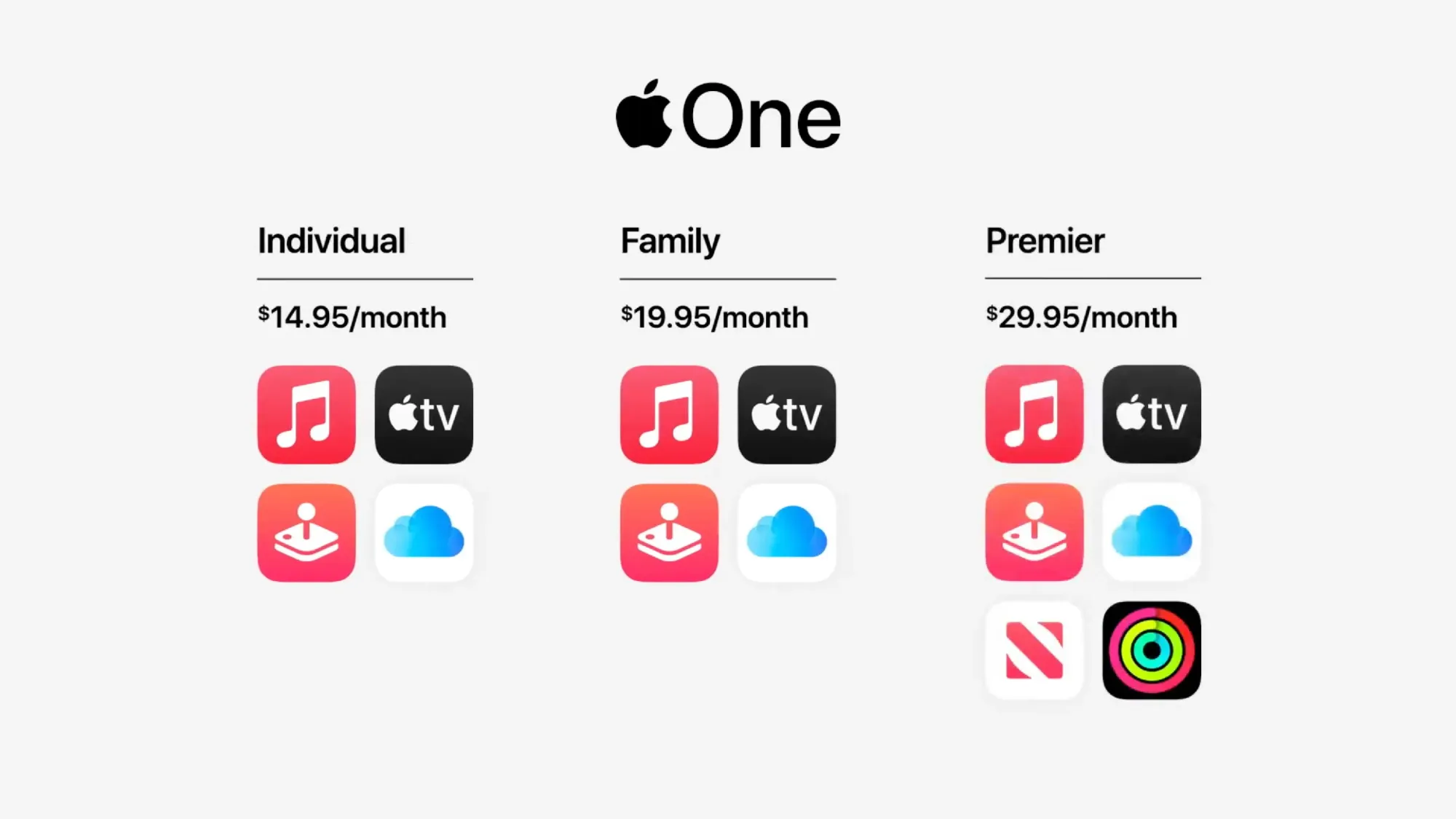

Apple One launched in 2020 as the company's answer to Amazon Prime—bundle everything together, make it cheaper than buying separately, and lock customers deeper into the ecosystem. At face value, it makes sense: the Individual plan at $19.95/month saves users about $9 monthly versus paying separately; the Family plan saves $11; the Premier plan saves a whopping $25.

But here's what the savings calculator doesn't tell you: Apple One exists because most of Apple's individual services can't compete head-to-head with specialized competitors.

Consider the reality check:

Apple Music vs. Spotify: Among Apple device owners, 41% subscribe to Apple Music versus 30% to Spotify. That sounds good until you realize Spotify has 626 million total users globally (246 million paid) compared to Apple Music's 108 million. Apple Music wins on its own platform primarily through deep integration and bundle inclusion—not because it's meaningfully better.

Apple TV+ vs. Netflix: This is where the contrast becomes brutal. Apple TV+ has maybe 25 million true paid subscribers (estimates vary wildly because Apple won't disclose real numbers). Netflix sits at 282.7 million. Apple TV+ accounts for just 0.2% of total TV viewing time in the United States—that's not a typo, zero-point-two percent—while Netflix commands 22% market share in SVOD. Netflix's audience in a single day exceeds what Apple TV+ sees in an entire month.

Apple spent $250 million on Masters of the Air. The show barely registered. They've invested billions in content that wins Emmys but doesn't win viewers. The quality is often exceptional—Ted Lasso, Severance, The Morning Show, For All Mankind—but having 271 titles can't compete with Netflix's catalog depth. Even Apple's "quality over quantity" positioning feels like corporate spin for "we're losing badly and trying to make it sound strategic."

Apple Arcade: Over 200 games available, and outside of hardcore gaming enthusiasts and families with kids, ask random Apple One subscribers the last time they opened the app. The silence is telling.

Apple News+: Magazines and newspapers that most people weren't paying for individually, bundled together in a service that still feels like an answer to a question nobody asked.

The pattern is clear: Apple One doesn't exist because these services are irresistible. It exists because bundling mediocre services with essential ones (iCloud storage) makes the whole package harder to cancel. That's not innovation—that's lock-in strategy dressed up as consumer value.

The App Store: The Golden Goose With a Target on Its Back

Here's the dirty secret about Apple's services success: A massive chunk of that 74% margin comes from the App Store's 15-30% commission on digital goods and subscriptions. The App Store is essentially printing money—some estimates suggest gross margins between 75-100% on App Store operations alone.

Developers call it the "Apple tax." Spotify, Epic Games, and countless others have spent years fighting it. And increasingly, regulators worldwide agree it's anticompetitive.

The UK's Competition Appeal Tribunal just ruled that Apple abused its market power by charging "excessive and unfair prices" from October 2015 through 2020, ordering damages potentially exceeding £1.5 billion ($2 billion). The EU's Digital Markets Act has already forced Apple to allow alternative payment systems in Europe. The U.S. Department of Justice has an antitrust lawsuit in progress that could fundamentally restructure Apple's entire App Store model, with a trial potentially beginning in 2027.

Apple's defense—that the walled garden protects user security and privacy—is wearing thin. The courts are increasingly seeing it for what critics claim it is: a monopoly using "anti-steering" rules and scare tactics to extract exorbitant fees from developers with no alternative distribution channel.

If Apple is forced to allow sideloading or reduce commissions significantly, that 74% services margin starts looking a lot less impressive. Economic analyses suggest that a 5% margin contraction would erase nearly $4 billion in annual profits. Over 10,000 apps have already implemented external payment links where allowed, signaling that developers and users both want alternatives.

The regulatory threat isn't theoretical—it's active, global, and accelerating.

The Identity Crisis: Hardware Company or Subscription Platform?

This is where Apple's services strategy reveals its deepest contradiction. Apple became Apple by making insanely great products that people wanted to own—devices so well-designed, so integrated, so thoughtfully executed that they commanded premium prices and inspired cult-like loyalty.

Services were supposed to enhance that hardware experience, not replace it as the profit engine.

But look at what's happening: iPhone sales were flat in fiscal 2024. iPad sales declined 6%. Wearables (including Apple Watch and AirPods) declined 7%. Mac sales grew slightly, but nowhere near services growth. The only segment showing strong, consistent growth is services at 13% year-over-year.

When your services division is growing 2-3x faster than your hardware, and generating nearly double the margin, the incentive structure becomes dangerous. Every executive review, every quarterly earnings call, every internal strategy session increasingly centers on: How do we grow services revenue?

And that's where things get insidious. Because optimizing for services revenue means:

- Prioritizing engagement over experience: The more time users spend in Apple's services, the better. But Apple hardware was never about maximizing screen time—it was about getting out of your way so you could live your life.

- Designing for recurring revenue: Hardware becomes the vessel to deliver subscriptions rather than the product itself. The iPad Pro isn't a computer—it's a platform to sell you iCloud storage, Apple TV+, and Apple Arcade.

- Competing with your own ecosystem: Apple Music competes with Spotify while Apple takes 30% from Spotify's subscriptions. Apple TV+ competes with Netflix while Apple takes a cut from Netflix sign-ups through the App Store (until Netflix pulled out). This isn't just anticompetitive—it's philosophically schizophrenic.

There's a word for when a company starts viewing its legendary hardware as merely a vehicle to sell monthly subscriptions: commoditization. And once you go down that path, the magic dies.

The Google Deal: Services Success Built on Someone Else's Innovation

Let's talk about the elephant in Apple's services portfolio: that $18-20 billion annual payment from Google to remain the default search engine on Safari and iOS. That's nearly 20% of total services revenue coming from... literally doing nothing except maintaining the status quo.

It's free money. It's also utterly dependent on Google's willingness to keep paying and regulators' willingness to keep allowing it. The DOJ's antitrust case against Google directly threatens this arrangement. If that deal disappears—and it very well might—Apple loses a massive profit center that requires zero effort.

This is the uncomfortable reality behind Apple's services "success": The most profitable parts aren't Apple's innovations at all. They're either monopoly rent-seeking (App Store commissions) or selling access to Apple's user base (the Google search deal). The consumer-facing services that Apple actually built and operates—Music, TV+, Arcade, News+—are the weakest links in the portfolio.

Subscription Fatigue and the Coming Reckoning

There's another problem brewing: subscription fatigue is real, and it's getting worse.

Consumers are drowning in monthly bills. Netflix, Disney+, Hulu, Max, Paramount+, Peacock, Spotify, Amazon Prime, YouTube Premium, and on and on. The average American household now has 4-5 streaming subscriptions, and people are starting to cut back.

When times get tough economically, subscriptions get scrutinized. And when people start canceling, bundled services like Apple One face a particular vulnerability: If users decide they don't want 2-3 of the bundled services, the savings disappear and the whole thing gets canceled.

Apple One has seen price increases from $14.95 to $19.95 (Individual), $19.95 to $25.95 (Family), and $29.95 to $37.95 (Premier) since launch. Each increase makes the value proposition harder to justify, especially when users realize they're paying for services they rarely use.

The company doesn't release Apple One subscription numbers (convenient, that), but anecdotal evidence suggests many subscribers are in it primarily for iCloud storage plus one other service, tolerating the rest. That's not a ringing endorsement of the product lineup.

Where Does This End?

Apple's services strategy has worked brilliantly from a financial perspective. Wall Street loves recurring revenue, and Apple's stock has benefited enormously from that 74% margin business growing at double-digit rates while hardware flatlines.

But there are three paths forward, and only one of them preserves what makes Apple special:

Path 1: Full Financialization – Apple leans harder into services, viewing hardware as a subscription delivery mechanism. Margins improve, recurring revenue grows, and the company becomes a more profitable, more predictable business. The trade-off: Apple becomes a different company. The hardware innovation that defined the brand becomes secondary to maximizing monthly active users and average revenue per user (ARPU). The magic dies slowly, but it dies.

Path 2: Regulatory Reckoning – Antitrust enforcement breaks apart the App Store monopoly, the Google search deal ends, and services growth stalls or reverses. Apple is forced to compete on merit with Spotify, Netflix, and others while earning dramatically lower margins on app distribution. The company survives (obviously—it's Apple), but the services gold rush ends, and the company must rediscover how to grow through innovation rather than rent-seeking.

Path 3: Rebalancing – Apple recognizes that services should enhance hardware, not replace it as the profit center. The company invests the services windfall back into making insanely great products that command premium prices and inspire loyalty. Services remain important but supporting actors, not the star of the show. Apple rediscovers its identity as a hardware company that happens to have great services, not a services company that happens to make hardware.

The Verdict: Genius With an Expiration Date

Apple's services strategy has been genius—for the past five years. The company identified a high-margin revenue stream, exploited its installed base, and built a recurring revenue machine that Wall Street loves.

But genius has limits. The strategy is built on:

- Monopolistic App Store practices facing increasing legal jeopardy

- A Google search deal that could evaporate

- Consumer-facing services that can't compete without bundling

- Hardware sales growth that has stalled

- A bundle strategy that disguises individual service weakness

That's not a sustainable foundation for the next decade.

The identity crisis is real. Every quarter that services grow faster than hardware, every earnings call that focuses more on subscriber counts than product innovation, every strategic decision that prioritizes recurring revenue over user experience—Apple drifts further from what made it Apple.

Tim Cook likes to say that services make the hardware more valuable. He's right. But the reverse is even more true: Hardware makes the services possible. Without the iPhone, iPad, Mac, and Apple Watch, there is no ecosystem to monetize. There are no captive users to cross-sell subscriptions. There is no premium brand to justify premium service pricing.

If Apple ever begins to see its hardware as merely a vessel for selling more subscription services, the game is over. Not immediately—Apple has too much brand equity, too much cash, too many loyal users. But slowly, inexorably, the company that changed the world with revolutionary hardware would become just another subscription business trying to maximize lifetime customer value.

That would be the ultimate identity crisis. Not because it fails financially, but because it succeeds at becoming something Apple was never supposed to be.

The genius of Apple's services strategy is undeniable. Whether it leads to existential crisis depends entirely on whether Apple can resist the siren song of recurring revenue and remember what made the company great in the first place.

Based on current trajectory, I'm not optimistic.

What do you think? Is Apple's services push a brilliant evolution or a dangerous distraction from hardware innovation? Let me know in the comments or on [social media platform].

Discussion